In its final years of operation, a particle collider in Northern California was refocused to search for signs of new particles that might help fill in some big blanks in our understanding of the universe.

A fresh analysis of this data, co-led by physicists at the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), limits some of the hiding places for one type of theorized particle – the dark photon, also known as the heavy photon – that was proposed to help explain the mystery of dark matter.

The latest result, published in the journal Physical Review Letters by the roughly 240-member BaBar Collaboration, adds to results from a collection of previous experiments seeking, but not yet finding, the theorized dark photons.

“Although it does not rule out the existence of dark photons, the BaBar results do limit where they can hide, and definitively rule out their explanation for another intriguing mystery associated with the property of the subatomic particle known as the muon,” said Michael Roney, BaBar spokesperson and University of Victoria professor.

Dark matter, which accounts for an estimated 85 percent of the total mass of the universe, has only been observed by its gravitational interactions with normal matter. For example, the rotation rate of galaxies is much faster than expected based on their visible matter, suggesting there is “missing” mass that has so far remained invisible to us.

So physicists have been working on theories and experiments to help explain what dark matter is made of – whether it is composed of undiscovered particles, for example, and whether there may be a hidden or “dark” force that governs the interactions of such particles among themselves and with visible matter. The dark photon, if it exists, has been put forward as a possible carrier of this dark force.

Using data collected from 2006 to 2008 at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in Menlo Park, California, the analysis team scanned the recorded byproducts of particle collisions for signs of a single particle of light – a photon – devoid of associated particle processes.

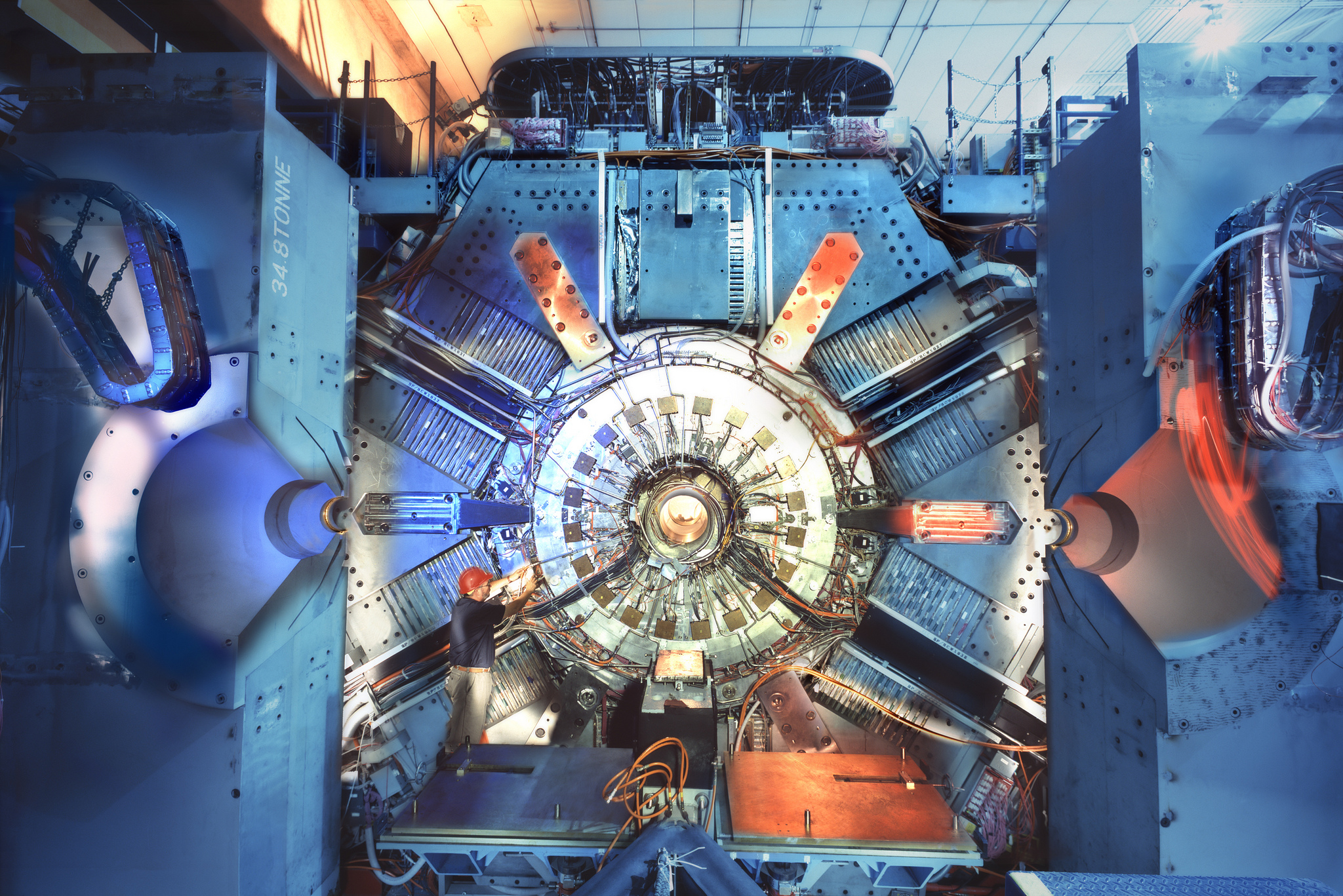

The BaBar experiment, which ran from 1999 to 2008 at SLAC, collected data from collisions of electrons with positrons, their positively charged antiparticles. The collider driving BaBar, called PEP-II, was built through a collaboration that included SLAC, Berkeley Lab, and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. At its peak, the BaBar Collaboration involved over 630 physicists from 13 countries.

BaBar was originally designed to study the differences in the behavior between matter and antimatter involving a b-quark. Simultaneously with a competing experiment in Japan called Belle, BaBar confirmed the predictions of theorists and paved the way for the 2008 Nobel Prize. Berkeley Lab physicist Pier Oddone proposed the idea for BaBar and Belle in 1987 while he was the Lab’s Physics division director.

The latest analysis used about 10 percent of BaBar’s data – recorded in its final two years of operation. Its data collection was refocused on finding particles not accounted for in physics’ Standard Model – a sort of rulebook for what particles and forces make up the known universe.

“BaBar performed an extensive campaign searching for dark sector particles, and this result will further constrain their existence,” said Bertrand Echenard, a research professor at Caltech who was instrumental in this effort.

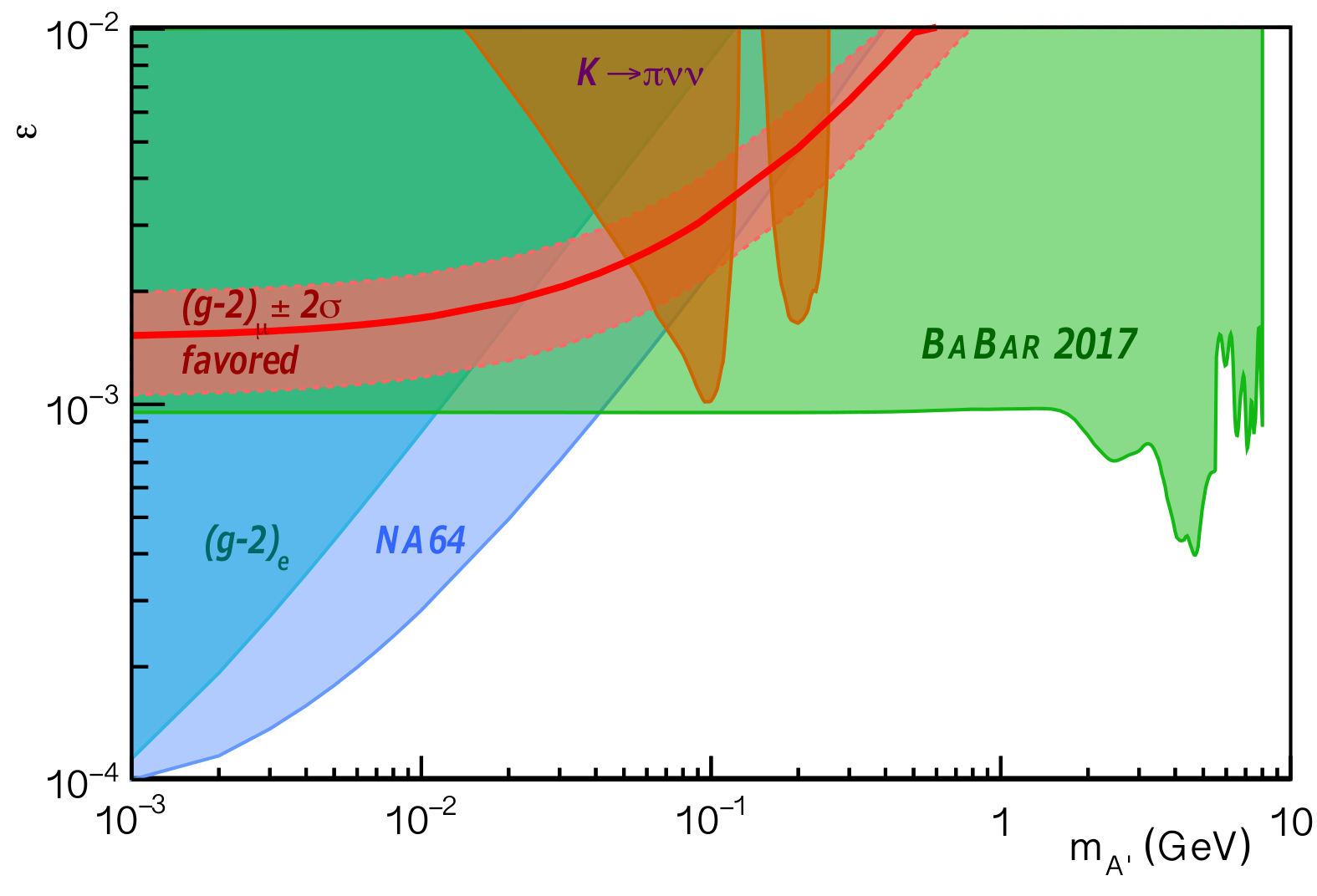

This chart shows the search area (green) explored in an analysis of BaBar data where dark photon particles have not been found, compared with other experiments’ search areas. The red band shows the favored search area to determine whether dark photons are causing the so-called “g-2 anomaly,” and the white areas are among the unexplored territories for dark photons. (Credit: Muon g-2 Collaboration)

Yury Kolomensky, a physicist in the Nuclear Science Division at Berkeley Lab and a faculty member in the Department of Physics at UC Berkeley, said, “The signature (of a dark photon) in the detector would be extremely simple: one high-energy photon, without any other activity.”

A number of the dark photon theories predict that the associated dark matter particles would be invisible to the detector. The single photon, radiated from a beam particle, signals that an electron-positron collision has occurred and that the invisible dark photon decayed to the dark matter particles, revealing itself in the absence of any other accompanying energy.

When physicists had proposed dark photons in 2009, it excited new interest in the physics community, and prompted a fresh look at BaBar’s data. Kolomensky supervised the data analysis, performed by UC Berkeley undergraduates Mark Derdzinski and Alexander Giuffrida.

“Dark photons could bridge this hidden divide between dark matter and our world, so it would be exciting if we had seen it,” Kolomensky said.

The dark photon has also been postulated to explain a discrepancy between the observation of a property of the muon spin and the value predicted for it in the Standard Model. Measuring this property with unprecedented precision is the goal of the Muon g-2 (pronounced gee-minus-two) Experiment at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory.

Earlier measurements at Brookhaven National Laboratory had found that this property of muons – like a spinning top with a wobble that is ever-slightly off the norm – is off by about 0.0002 percent from what is expected. Dark photons were suggested as one possible particle candidate to explain this mystery, and a new round of experiments begun earlier this year should help to determine whether the anomaly is actually a discovery.

The latest BaBar result, Kolomensky said, largely “rules out these dark photon theories as an explanation for the g-2 anomaly, effectively closing this particular window, but it also means there is something else driving the g-2 anomaly if it’s a real effect.”

It’s a common and constant interplay between theory and experiments, with theory adjusting to new constraints set by experiments, and experiments seeking inspiration from new and adjusted theories to find the next proving grounds for testing out those theories.

Scientists have been actively mining BaBar’s data, Roney said, to take advantage of the well-understood experimental conditions and detector to test new theoretical ideas.

“Finding an explanation for dark matter is one of the most important challenges in physics today, and looking for dark photons was a natural way for BaBar to contribute,” Roney said, adding that many experiments in operation or planned around the world are seeking to address this problem.

An upgrade of an experiment in Japan that is similar to BaBar, called Belle II, turns on next year. “Eventually, Belle II will produce 100 times more statistics compared to BaBar,” Kolomensky said. “Experiments like this can probe new theories and more states, effectively opening new possibilities for additional tests and measurements.”

“Until Belle II has accumulated significant amounts of data, BaBar will continue for the next several years to yield new impactful results like this one,” Roney said.

The study featured participation by the international BaBar collaboration, which includes researchers from about 66 institutions in the U.S., Canada, France, Spain, Italy, Norway, Germany, Russia, India, Saudi Arabia, U.K., the Netherlands, and Israel. The work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science and the National Science Foundation; the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council in Canada; CEA and CNRS-IN2P3 in France; BMBF and DFG in Germany; INFN in Italy; FOM in the Netherlands; NFR in Norway; MES in Russia; MINECO in Spain; STFC in the U.K.; and BSF in Israel and the U.S. Individuals involved with this study have received support from the Marie Curie EIF in the European Union, and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation in the U.S.

###

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory addresses the world’s most urgent scientific challenges by advancing sustainable energy, protecting human health, creating new materials, and revealing the origin and fate of the universe. Founded in 1931, Berkeley Lab’s scientific expertise has been recognized with 13 Nobel Prizes. The University of California manages Berkeley Lab for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. For more, visit www.lbl.gov.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.